1.

Areng Valley

The Areng Valley is a roughly 25 kilometers long valley in the southern Cardamom Mountains. The Areng River is winding through the valley, from north to south, inmiddle of a plain which is elevating to the east and west after a few kilometers and rising up increasingly steep towards two bordering mountain ridges.

The Areng River. Image by Asienreisender, 2/2016

Areng Valley is yet a remote landscape. In it's natural state it was covered mostly with tropical rainforest and is now inhabited by a not exactly known number of people in six hamlets; estimations count 1,300 people, others count up to over 2,000. Coming from the district town (rather village) Thmor Bang, a rough dirt road leads over a mountain ridge into the valley. The next hamlet, Tree-Ak, is 18km away. Another entry to the valley is a desolate dirt road or track which comes from Chi Phat. There is no other access to the valley, except maybe two abandonded trails in the very north. One has to keep in mind here that the Areng Valley is part of the 'Central Cardamom Mountain Protected Area'. The valley is home to a number of rare and endangered animals and plants.

The Image Top Right shows an Indochinese Tiger in Kampot Zoo. In the not too far past there were many tigers living in Cambodia's forests. Norman Lewis wrote, that they sometimes went into towns at dusk or nighttime (Lewis, Norman: A Dragon Apparent, 1946). Nowadyas, tigers in the wild are at the brink of extinction. It's highly improbable to meet a tiger in Areng Valley. In April 2016 World Wildlife Fond declared wild tigers in Cambodia as extinct. Image by Asienreisender, 6/2013

The tiger image is not displayed in the mobile version of this page.

Tropical Rainforest in the Areng Valley

Despite the months long heat in the dry season there is still a steady mist over the rainforest. The rainforest produces partially it's own rain, evaporating humidity at certain regions which pours down at others. Additionally the mist comes down as a slight morning dew.

Here, in the mountains, it gets at night and the early mornings quite chilly. One night there was even a slight rain for about two hours before sunrise. The opposite mountain ridge is the easter border of the valley.

Great hornbills appear here many times, often quite close. Image by Asienreisender, 2/2016

2.

The Nature and Human Impact

The landscape is so remarkable, because the impact of modern civilization is still relative small, considered we live in the 21st century. The rainforests in the valley are widely destroyed, due to slash-and-burn agriculture of the villagers, who gain more and more land, and nonlocals, who come as middlemen to prey on the nature. A rapid population growth also demands it's tribute.

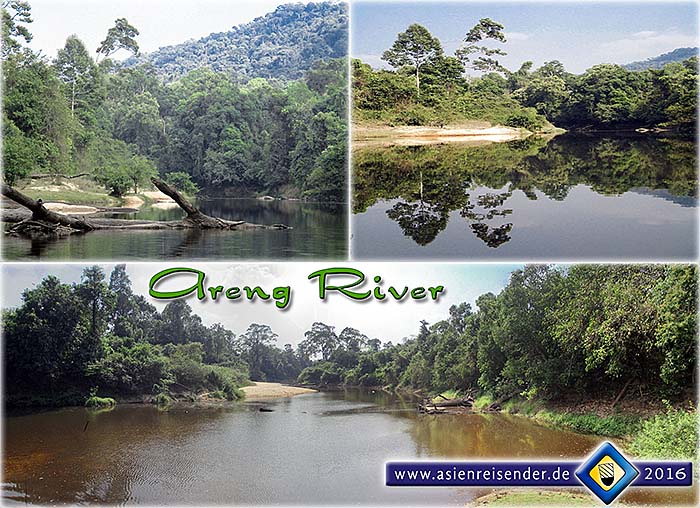

The Areng River

The Areng River, who comes from the northern end of the lengthy valley, is a widely intact forest river. There is comparably small impact, although it's already concerning and certainly increasing. The river drains at Botum Sakor National Park into the Gulf of Thailand.

At the end of February the water level is shallow. Rowing along here in the kayak, the boat run repeatedly on the sandy ground or on wood. A great deal of forest trees, who fell into the water, slowly rot away. The current is so slow that one can not recognize it. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, 2/2016

Additionally happens the logging of the grand, majestic jungle giants. Access paths are hewn into the forests to the most valuable trees who get cut then and transported in pieces out of the valley. The logging activities happen at daytime; on my excursions into the valley off the road I heared motorchains in the green. The transport out of the valley is then done at nighttime, and, according to a local witness, police is involved. The process of logging is here meanwhile so far advanced, that the most precious trees are long since cut and it's more and more about the last bigger trees towards the mountains.

The trade in rare woods is profitable. While in the past five man with axes ned a whole day or even up to a week to cut a single large tree, nowadays one man alone can cut three to five trees per day. STIHL motorchains are notorious as logging tools. However, the chainsaws are expensive and the villagers often do not have the business conncetions to the illegal networks. Here come outsiders into the play. Politicians, army and police officers who know the networks, equip the villagers with the necessary tools. The villagers do the work, get a petty share of the business, and the outsiders organize the transport out of the 'protected area' and supply the black market. Many of the animals caught here and of the wood goes to neighbouring Thailand, a rich country with purchase power. You find more on that on the Bokor Mountain page.

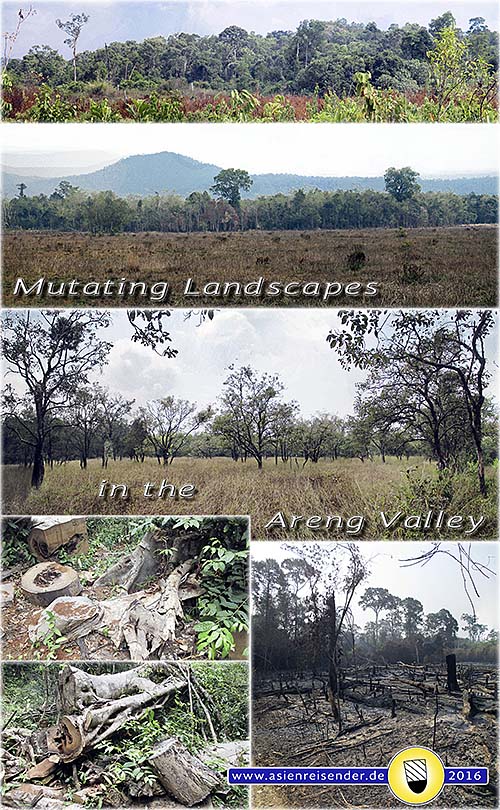

Changing Landscapes

The landscapes in the valley are altering in a rapid speed. Few patches of virgin forest are left; particularly along the river is a seam of still healthy looking forest.

Parts of the area who have been logged, slashed and burned years ago, partially decades or more before, regrew into poor grassland, sometimes with single trees scattered around. Everywhere are traces of recent human impact; many spots are burned down, ashes are still in the air. Bottom left a recently cut tree; woodshavings are still around. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, 3/2016

The trade with wildlife is also very lucrative, and many rich, particularly Chinese businessmen, are willing to pay a high price for seldom animals. They get eaten in luxurious Chinese restaurants as 'special meals' or they get killed to gain Chinese 'medicine' from them.

At the junction along NH48, where a new, broad dirt road splits up towards the valley, is a checkpoint placed where vehicles, who are leaving the mountains, are (neglectfully) controlled.

Therefore seems to be no mentionable immigration into the valley yet, because for most people the absence of electricity, running water and mobile phone services is nowadays no more bearable. And exactly that is one of the points who make the area so valuable.

As higher one climbs into the mountains, as richer and purer the nature get's. The mountain slopes are the last refuge of the rainforests, because it's more difficult to access it and bring the precious trees out. Also slash and burn does not make sense at the slopes, for they are not good as arable land.

Nevertheless, at many spots are fires burning, every day. The accumulated smoke fills the valley with a sometimes quite thick haze which is certainly also a serious impact on everyones health. Partially the sight is very limited and the bordering mountains are barely to see anymore. The atmosphere in this time of the year, February / March, is spooky, unreal, apocalyptic.

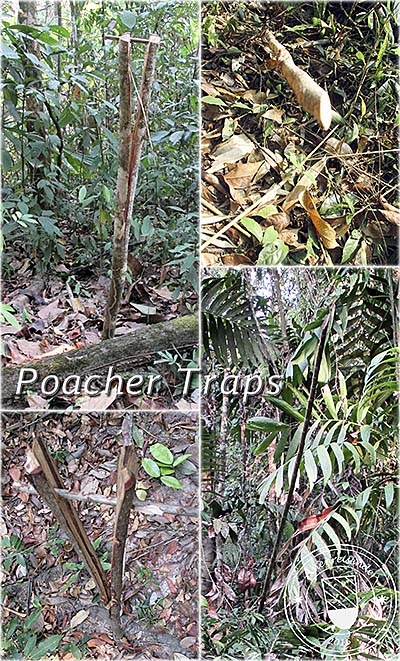

Apart from the ongoing destruction of the natural forests by logging and fireclearing, poaching happens as everywhere where people live. Wild animals are a traditional part of the local's diet and they don't see the point to change their livestyle according to that. Traditionally the jungle is seen as a common resource where anybody can take out for free what he finds. When hiking in the jungle, I found an incredible high number of wooden traps.

Deforestation in the Areng Valley

Along the single dirt road which leads along the valley, it looks at some parts already so. Leaving the road and following the endlessly many tracks, it looks everywhere similar. Slash and burn exposes the fragile toplayer soil of the tropical rainforest to erosion. In the next rainy season most of the fertile soil is washed out. What remains is the poor, often sandy sublayer, which is poor in nutrients. Agriculture on this acreage is not longer possible than for two to five years, then the soil is completely exhausted. The former rainforest can not recover. It would last eons of years to re-evolve a fertile ground. Instead savannah, grassland or a much poorer secondary forest regrows. Seems, that shows more and more the future of the fragile ecosystem in the Areng Valley. Image by Asienreisender, 2/2016

3.

Animals

The Great Hornbill

They are frequent here, and easy to hear due to the whisking noise of their wings. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, 2/2016

Nevertheless, the Areng Valley is still a grand and phantastic natural reserve with a number of rare animals living here. Most prominent are the great hornbills, who appear here all around. Every day I saw them several times. They are easy to hear, for their wings make a certain, wiping noise in the air, and they are quite big birds.

Another prominent animal is the Siam crocodile which once lived in many rivers in Southeast Asia and is meanwhile almost extinct in the wild, reduced to one or two remaining habitats. Everyone claims the Siam crocodiles would be harmless creepers and do no unprovoked harm to humans. In the wider area live still herds of Asian elephants, who walk seasonally along certain routes also across the Areng Valley. Bears live here in the mountains, and in the remotest areas are still Indochinese tigers and leopards, although not been seen since years by all villagers I asked for. Cases of attacked humans by the huge predators are here unknown. Hundreds of more species, of who 31 are globally critically endangered, are living in the valley.

A few hours on the Areng River, paddling the shallow stream a piece up and down, made a deep impression. Many animals live in the trees around; one sees a lot of birds, some of them quite big. There are occasionally monkeys in the treetops and I saw a couple of otters, if I got that right, who disappeared most quickly when seeing the kayak. They were to hear running away in the underwood for a while. A larger snake wound down the opposite river bank and slipped slowly into the river. Squirrels move in the trees. At one occasion, having a bath in the river, a leech tried to stick on my leg, but I could escape it. The leech was quite big, much bigger than the ones in Khao Sok National Park or on Pankgor Island. Some of the birds I saw in the valley looked like birds of paradise, with long, fabulous tails, but birds of paradise don't live here. Most of their kind is endemic in east Indonesia, beyond the Wallace Line. No human soul around, no civilization noise, just the sounds of the nature.

A Baby Siamese Crocodile

Unfortunately I didn't see one of the rare lizards; their time is probably rather in rainy season. So far I know, they live in the lower parts of Areng River, not further north than at Prolai. This photo sticks at the wall of Chumnoab's community center. Image by Asienreisender, 3/2016

However, also at the river is human impact to see. On the river section I went up and down by boat were three fishing nets spanned over the whole width of the stream. At several places I saw the river forest cut over a few meters, some of the cut trees were fallen into the river and left abandoned there. At one spot an underwood fire was burning. Certainly set by a villager.

Spending the nights in the jungle, partly sleeping in a hammock under the trees, partly listening the voices of the nature, made the deepest impression. A lot of animals make their sounds and communicate over large distances. Some of the noises are really remarkable and unforgettable. It's the largest contrast to the usually omnipresent music of our times, which is merely an insane, soulless and alienated stress, poison for the mind. Being only a few days in the nature refreshes the senses for what is real and good and fills the mind with serenity and a deep energy.

4.

Population

The local people are ethnically slightly different from the Khmer majority in Cambodia. They belong to the Chong and Phor tribes, who are being considered as Khmer Daeum, means 'original Khmers'. They immigrated centures before to this remote area to escape capture and slavery threatened by an invading Siamese army. Their skin colour is dark, often very dark, almost black. Many have very Indian face traits.

Noodle making in Areng Valley. The locals grind rice to flour and blend it with hot water; then they squeeze the dough through a simple metal grid. Image by Asienreisender, 2/2016

The local's religion is, although officially buddhist, in fact animist. There are, after what I heared, only two buddhist monks living in a small wat in Prolai (see the map). Before they were living in the northermost hamlet of Chumna, but, after what I heared, the villagers couldn't support them. These buddhist monks live from alms and do not produce food in their temples, as the medieval European monks did in their monasteries.

However, in their behaviour the local villagers are not much different than the Khmer majority in Cambodia. They are widely alienated primitives with no manners. They have no sense for the nature but to butcher it out for their daily needs and moreover for money. It's clearly to see that these tribal people do not live with the nature, but against it. There is little understanding for their surroundings, ask them what you want to know, and in the verymost cases it turns out that they have not the faintest clue about the environment they live in. Getting supplied with more and more modern consumer crap, all wrapped in plastic, these people litter wherever they go, stand, walk, sit, lie. Around any of their shacks stretches a filthy litter belt, occasionally sloppily swept on a heap here and next time on a heap there and burned. The plastic smog creeps over the tables, the food, into the dwellings, the kids breath it, but there is no concern. The way they spoil their environment is a clear outer expression of their inner, mental condition.

Tribalism in our times

Encountering a tribal population in the Areng Valley, it would be naive to assume they were still living in a 'natural state', as people did in prehistoric times. The ethnologist Adolf Bastian observed already in the 1860s what he called a 'Weltenbrand' (a world's fire), which destroyed all other cultures on the globe. This fire has been set by western colonialism, putting western culture over the whole world.

A Case of Wood Theft

This pretty muscle man at the southern end of Chumnoab didn't like me to make this photo. Here he holds already his hand in front of his face, to avoid being identified. He stopped and wanted to confiscate my camera. What is out of question, of course. It turned out that he stole the planks on his motorbike from the next wooden bridge. He followed me and approached three times to take my camera over; last time I saw him in Tree-Ak at the post of Wildlife Alliance. Seems, that is his place, for he drove there repeatedly the village road up and down, no shirt on but a golden necklace around his neck, and pested me a last time. I made the photo actually because of the remarkable mode of transport. Image by Asienreisender, 3/2016

Western culture is in it's marrow coined by capitalism. Capitalism is a totalitarian system, although we are not used to see it so. Totalitarian is a doctrine who is targeting to subdue all other doctrines and concepts of life with the goal to conquer and exclusively dominate the whole world. It occupies one's mind thoroughly and deeply influences everybodies privacy. Everything is about money in our times, in our contemporary global society; money is the central mean of communication in all human relationships.

What is left of local cultures is merely superficial rituals from the past who have lost their meaning. It's often good for tourist events or falls gradually into oblivion.

The villagers in the Areng Valley depend on money as anyone in our times. A prehistoric lifestyle is widely in accordance with the nature, but it's hard. That's why life expectancy was so low in the early times of mankind. Imagine just one has a toothache, or an appendicitis. Many people died by diseases who are nowadays easily curable - provided you can pay the doctor. (For an insight into a prehistoric culture in Southeast Asia check the article on Ban Chiang).

Once comming in contact with money, a society gets corrupted. Money makes such a difference in what one can do (and own). It's not only the primitives who are dazzled by the great consumer promises of the commodity producing system. Consumerism is one of the modern fetishes of the secularian religion of the free market society. Riding a motorbike is a thousand times better than to walk, or? Electricity, radio, karaoke TV (KTV), mobile phones, range rovers, big villas, buying people, buying for fun, and, and, and... there is no end of that. Modern people forgot their real needs and poison their minds everywhere with these insanities, and there is principally no difference between the primitives in the Areng Valley, the western middle-class and the bankers at Wall Street.

At least with the invention of money, greed has crept into the valley. Those, who come in contact with the yet trickling tourists who visit Areng, smell business and turn their behaviour quickly into an impertinent marketing attitude.

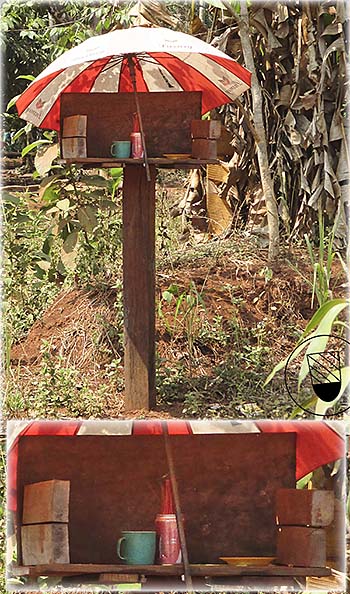

An Animist Spirit House

In the buddhist countries of Indochina are spirit houses a common appearance. But they are absolutely not of buddhist origin. They represent a religious atavism, maintained from the ancient times before the two high religions Hinduism and Buddhism were established. Here we see a little animist sanctuary in a pretty simple, 'sober' state, to the very contrary of those highly decorated spirit houses in neighbouring Thailand with all the many buddhist, hindu and local and individual idols in them, together with donations of food, drink, sometimes cigarettes and whiskey and more. Images and photocompositon by Asienreisender, Chumnoab, 3/2016

One afternoon, after a long walk through the western part of the valley at Prolai, I had lunch in the (only) restaurant in Chumnoab. Food was lousy, barely edible, big chunks of boiled bones with almost no meat on it, with some green and old, cold, clumpy rice. Food is generally poor in Cambodia, and particularly in the countryside it's hard to get somewhat half-way reasonable to eat. I couldn't swallow half of it. Asking for the bill (should have done that before ordering, but mistakenly trusted them), triggered the two women there having a discussion. They were talking about how much they could demand, and made me then a 100% markup. Their whole expression had changed suddenly, no smiling anymore as before, rather the look of crocodiles on their prey. Avoiding to talk to me directly, they let the sum getting (unnecessarily) translated by one of the activists from Mother Nature. For him that seemed to be completely fine. I didn't complain, but the message was clear: it's perfectly okay to rip off visitors.

On my several days long hikes through the valley I made repeatedly acquaintances with this mentality. It's the same here like everywhere in Cambodia. I also didn't find the locals anyhow more supporting or willing to help than elsewhere in this country. But also I found other shop owners honest; one never knows.

There is a short interview on youtube, in which Alejandro Gonzalez-Davidson talks to a local woman in Somrong. She gives five arguments against the planned Areng Dam: 1) I don't leave my place, because all the land around is mine; 2) all the land is mine; 3) it's all my land; 4) it's my land; 5) my land. She couldn't express herself less egocentric and selfish. She does not even speak about her family; it's just about her personal, private property. What could be more petty bourgeois? On the question if she would use chemical pesticides she declines that, for the mere reason that she can't affort them, as she adds (otherwise, of course, she would).

The short video sequence gives also a lively impression of the pretty limited IQ of the majority of the local population (what is Cambodian standard, and I am sorry to say that, because I suffer personally every day, often quite heavily, under it).

Kalyanee Mam, the director of the film 'Fight for Areng', describes the villagers as having a

"very beautiful live, completely connected to nature"; as the "most rooted and grounded people I have ever met" (...) "for their connection to the land". "They feel so grateful for nature, because everything they have, comes from nature". Note, she does not say 'all they are, comes from nature', but 'everything they have'.

She further on adds "Do we want to pass on [to coming generations] a desolate desert, or do we want to pass on a heritage, that is loving of the earth, loving of the land, loving of nature". The alternative is not given. A flooded valley wouldn't mean a desert, and the villagers are straight on the way to change the valley into a 'desolate desert'; in great parts they were already successfull.

An Animist Festival

The People of Southeast Asia like festivals, and there are many holidays and other occasions for excessive partying. It's usually coming with different kinds of religious rituals. Here, at early March, the sequence shows an animist festival in Chumnoab.

Preparations had been done hours before, and at late lunchtime I met one of the villagers, who is dancing here, in a restaurant. He was already full-drunk (and importunate), what was apparently part of the party preparation; there was plenty of rice whiskey around this day. Seems, they need the booze to see the spirits they belive in.

The spectacle here is just at the very beginning. Wooden instruments are used and left hand, not to see in the dark, are the villagers idols placed for worship. The tamtam went on the whole night and became for a longer time very noisy. The booze and whatever else they may have taken brought the partyers into ecstasy. The sound they produced was accompanied by many jointly howlings, somewhat of the kind the Indians do in the 1990 movie 'Dances with Wolves'. Altogether it didn't sound harmonic, rather like a more aggressive war dance. Video by Asienreisender, 3/2016

In a following sequence a Chong woman with her baby is shown on a small boat on the Areng River. She repeats that: "...everything that I have, is a gift from nature." Again 'to have', not 'to be'. And that's correct. They fill their pockets with the riches of the nature as good as they can. It's a completely materialistic language. It expresses very clearly the separation between subject and nature. A few more hollow phrases follow, for example about the peoples love for nature and the love of nature for them (how does nature expresses her love to them? Is that when wild animals run into their forest traps, or when great habitats are burned and fall out in rains of ashes?).

Both villagers are dressed not in traditional clothes, but completely modern, except of the woman's Khmer scarf. Her husband, in the background quietly rowing the boat, wears a shirt and looks not much different than these smart shadow banksters from the microfinance institutions in Cambodia, who supply the villagers with easy money for consumer goods. The high price of the money (interest) has to be payed back, and what else do the villagers have to pay with than the treasures of the oh so beloved nature (and the hopes for a soon rising tourist industry with the common rip-offs).

Nothing could be more wrong than the image produced here. The whole film is an concoction of a false understanding, misinterpretations, mendacity and wish thinking. In the way it is made, it's the perfect appeal to estranged Westerners who are desperately on the search for harmony with the nature. The good, innocent, virgin villagers, who live in harmony with the nature, contrast the bad outer world with the profit greedy government and the corporations behind. Such distorted narratives are a big market themselves, by the way, particularly for the tourist industries.

For the villagers the dam would of course mean a desastrous impact on their lives. And it is a good thing to support them in their resistance against the dam. But it's wrong to mystify, and ridiculous to romanticize them.

For the nature there are two alternatives. The slower death due to the disastrous, unsustainable livestyle of the villagers themselves, accompanied by tourist impact, or, worse, the quick death if the valley should be flooded and the slopes being exposed to more logging.

Jungle Guides in Areng Valley

A jungle guide in Southeast Asia is not at all to compare with a nature guide in a western country. In difference to the latter they have no qualification at all. Their only point is that they are native to the region and know the forest tracks. At least some. Why do they know the tracks? Well, they go in there from time to time. Why are they doing that? That's certainly not because they 'love so much the nature'. They have a purpose. That is to take out wood, fruits, herbs, mushrooms, animals, do fishing and so on. That is so far a traditional livestyle. The suspicion is close that this has an intersection to poaching and logging. Who is used to go into the forest for food is certainly predestinated to take more than he and his community need when it pays out.

On my first excursion into the valley I went with a group of locals into the forest. They were pretty noisy, the last one cried to the first one and vice versa; the leading guide walked much too fast and he had two dogs with him - a guarantee not to see wildlife, for all the wild animals scare the dogs. However, I wouldn't have found some places in the forest without their help; besides, one can get lost here, when loosing orientation or forgetting exactly the way back, what can turn out sometimes unexpectedly difficult.

Too many people in the night camp where too noisy, particularly after enjoying the unavoidable rice whiskey. The food was not edible, because they didn't boil the chicken long enough and it remained raw.

Do you learn what about the rainforest? Yes, by your own observations and experience, not at all by the guides. They don't tell what and they know very little. What they know they have seen as boys by other villagers. The forest nature is divided in two parts: can eat or sell, no can eat or sell.

On the second trip into the valley I had the plan to see three certain sites. One was the jar site of Rong Chomneang. Asking for a guide at the community center in Chumnoab, a proto-tourist village, they offered me a motorbike trip 15km deep into the jungle [!]. Of course, they go as deep as they can into the nature with their beloved motorbikes.

All information I got out about the planned trip was inconsistent. Again, the locals never explain what. They expect one just to follow them and they do what they want. Like the drivers here - the driver is always the boss. And they never think ahead. Meeting three Khmer tourists who hired a guide who failed to bring them to a certain waterfall (rapids in the Areng River, three of them, who are called waterfalls) didn't make me happier. This time I decided against a guide and made my hikes alone.

The habit to go with the motorbike whereever one can is typical for the Khmers generally, and I have never met an exception. The young middle class people from Phnom Penh do it as well as the activists here. When I first met a member of Mother Nature, he talked about the spirit of going into the natural forest and that it requires respect and a good heart for the nature. Later, I learned that that is compatible with driving with the motorbike into the forest, also when it is easy to walk or to use a bicycle.

5.

Areng's Future

So, the outlook for the nature is not that promising. The Areng Valley is under severe threat. It has yet survived two attacks of modern industries. The first came by a mining company who planned grand-style titanium mining in the valley's mountains, affecting up to 20,000 hectars of the valley. Another big project of a larger scale is the planned Cheay Areng Dam (see below), which could be fended at least until 2018 - the year of the next general elections in Cambodia.

If the regime sends it's troops in 2018 or later to evacuate the valley, the villagers will suffer a great misery. The last of their places they will see is that their wooden homes burn as they burn frequently the forests. From then on they are displaced people, and it's questionable if they can establish a comparable life in another part of the Cardamom Mountains. Probably many will end up as city dwellers, either in Koh Kong or, rather, once more filling the slums of Phnom Penh, the ugliest place in the country.

In a smaller scale, the villagers do a great harm to the valley's nature, and they are clearly going to eat it all up.

But also without big projects the natural environments will further degrade without a doubt. Development creeps into the hamlets and brings improved and paved roads, more traffic, electricity, mobile phone towers, internet, more visitors, investment, din and more pollution. Tourism is yet on a very low level, the Areng Valley is still kind of a secret destination. But it's a promoted destination already and the first small touristic groups come from Koh Kong or Phnom Penh. Young middle-class Khmer come in small groups on their own motorbikes, fewer Westerners book a package tour and go into the forests and to the river. They consume, produce litter, are noisy, disturb animals, smoke in the forests, set their alarm clocks in the jungle as if they would have to go to office in the morning, and so on. There will be soon the heavy smell of tourist money in the air. That triggers next a gold-digger atmosphere, shaping competing villagers who boast to each other how much they got out of certain tourists. The behaviour then changes from natural to pushing visitors to buy services and not accepting a simple 'No, thank you, I don't need that'. Until now, I personally found only one villager already infected by that kind of ambitions; not any different from the touts or motorbike drivers in Phnom Penh, he dreams of easy money by moto driving. The poisonous impact of tourism follows always the same pattern. A comparable place is Bukit Lawang on Sumatra, where the touristic development was already advanced in the mid 1990s. In Bukit Lawang practically any male local between eight and eighty years old is a self-declared jungle guide.

The advocates for tourism often argue, they would promote 'ecotourism'. It's sustainable and protects the environment, it empowers local communities and promotes education - sounds very good. There is just one thing about ecotourism. It's business. It's never sustainable, because it's for profit. It means growth. It means pollution. It's more honest to call it 'eco-business'. It's a contradiction; the two things don't fit together. Ecobusiness is just another impact on the nature. It's not more 'eco' than palmoil plantations with their green fuel production. Ecological is only to let the nature alone in an untouched state, and by no means do business with it. Business is the archenemy of the ecology, because it's parasitic and lives from nature's exploitation.

It's a pity and sad thing that the only way to protect such a valuable nature reservation is to set up the strictest measures, comparable to those in Malaysia's peninsular national park Taman Negara or Penang National Park. But also there, it seems, is the nature more and more in retreat, isolated patches of rainforest surrounded by huge palmoil plantations.

6.

Damming the Areng River

Since years is the talk about a dam on the Areng River. The first time I personally noticed it was due to a petition by 'Rainforest Rescue', in 2014. First China Southern Power Corporation planned a dam, but didn't built it. Profitability wasn't given, the construction wouldn't be efficient. Then the Cambodian government found another company, the state owned China Guodian Corporation (Sinohydro Recources, in cooperation with it's Cambodian partner Pheapimex, notorious in land conflicts in Cambodia), who is willing to undertake the project, which is supposed to cost 300 million dollars.

The Cheay Areng Dam

The installation of the Cheay Areng Dam would mean that 20,000km2 forested area would be flooded, of who greater parts are under 'protection'. Hundreds of species, of whom 31 are globally threatened, would be affected. The last wild Siam crocodiles, who live here, would extinct.

The activist group Mother Nature does not only fight against the construction of a mad dam in the valley. They have a comprehensive programme for the preservation of the valley's nature. One example is the blessing of trees in cooperation with buddhist monks. The trees get an orange cloth bound around their stem which has a strong symbolic power (This tree has one, but it's not to recognize on the poor photo). For more information about Mother Nature click the link to their homepage. Image by Asienreisender, 2/2016

A couple of villages in the Areng Valley are inhabited by people of the Chong and Phor tribes, ethnic minorities who are ranged in as Khmer Daeum, 'original Khmers'. They speak an ancient Khmer, which is still existing here because these people lived over centuries in isolation. They settle here since centuries and were immigrated when Siamese armies conquered greater parts of Cambodia from the 15th century on. It was their choice to escape slavery and deportation to Siam (see also: 'Hill Tribes in Southeast Asia'). These people would be resettled into areas who are less good as farmland, to say only the least.

With the dam come more roads who give poachers and loggers easy access to the remaining forests. One sees this process already in the example of Stung Atai Dam at Ou Soum. Still, the costs are higher than the prospected gain of the relatively low-productive 108 megawatts dam. What makes the government then deciding for such a dam?

Well, there are precedence cases, like that of the Sanyaburi Dam in Laos (see: 'Damming the Mekong') or of many dams in India, namely the Sardar Sarovar dam at the Narmada River (read also: Arundhati Roy: 'The Cost of Living'. Roy gives a detailed description of the effects of the Sardar Sarovar dam). The pattern is that: The government agrees with a (foreign) company, involving international banks (including the World Bank), to built a dam. An expertise is ordered by a firm who is close to the banks. The expertise will play down the human and environmental costs and stress the benefits. Now the government get's loans from the bank(s) and pays the costs. The costs will be (much) higher than first expected. Means more loans. The government has to pay back the loans and interest over a long time, and it will be very expensive. It's good for the banks, the construction company and for those highest functionaries in the government apparatus who get, let's say, some 'rewards' from the other partners involved. Inofficial 'gentlemen agreements', you know what I mean. It quickly turns out that the dam is disfunctional, brings far less money back than first claimed and the harm for thousands of people and the nature is immense. But all that doesn't matter; rich national and international circles made 'good business'. And that repeats again and again and again, although the experiences are always so negative. Our socialeconomic system generally promotes a 'healthy' economy for the price of an insane society.

Resistance Against the Dam

About 2,000 people live in the Areng Valley, of who 1,600 will loose their homes if the dam is built. Naturally they are the core of the resistance fight against the mad project, for they have to loose the most. One can not expect much from the many NGO's in Cambodia when it comes to serious actions. NGO's are most usually agents of foreign business interests. They don't risk serious trouble with the government. NGO's can be expelled, what would mean the end of their work here. There is also for any foreigner the threat of being deported from the country, as it happened to Alejandro Gonzalez-Davidson, a co-founder and key-activist of Mother Earth.

Mother Earth seems to be the only environmental and human-rights group which did consequently and actively resist against Cheay Areng Dam. They organized and informed the local villagers and created a media campaign, informing the Cambodian youth about what's going on in the valley. Activists sent five times surveyers and construction workers back by surrounding them or blocking the road and making it impossible for them to start work - direct action without violence.

That led finally to the arrest of several activists who got only free by signing an agreement to cease their activism. Alejandro Gonzalez-Davidson was detained and deported from Phnom Penh International Airport three days after his visa was run out. Unwanted destination: Madrid, Spain. It was clear to him that a visa renewal wouldn't be granted by the Cambodian authorities. Alejandro Gonzalez-Davidson, who lived since twelve years in Cambodia and speaks Khmer fluently, escaped his guards on Suvannabhumi Airport in Bangkok. Now he is continuing his work from Thailand and the USA. The activists enjoy large support in the Cambodian public, particularly among the younger generation.

Primeminister Hun Sen first jangled he would send artillery into the Areng Valley if necessary, to break resistance. It happened repeatedly that the army was sent to clear villages to make the way free for corporate land grabbing in Cambodia. Next day, under pressure, Hun Sen expressed moderately that the plans for a dam in the valley would be postponed. He added that there mustn't be any talk anymore about the project.

However, pressure on the Cambodian activists of Mother Earth are going on. And there are more issues, like sand dredging in the rivers of Koh Kong.

7.

A Heavy Way Back...

Since transport is poor here and the way out to Thmor Bang leads through parts of the Areng Valley, I decided to walk back these 29km. Best time to leave is, of course, with the first sun rays. But I had to pay my bill for the guide and food first. So, I was forced to go back from the river banks, where I had spent the night, to the village. But none of the locals there was able to make me the bill. Next I walked up and down the village road on the search for a competent money collector, but was sent to and fro. When I finally found the right guy(s), they ned a long, long time for that little piece of paperwork. To make it short, alltogether I lost three hours for the blasted thing, and not even had a breakfast in the time. Leaving at nine o'clock, when it was quite hot already, proved to be almost fatal.

Another fellow on the way who fell in serious trouble. Image by Asienreisender, 2/2016

Being a good walker I made the first 18km or so quite well, but there was a mountain ridge to cross, diverting the dirt road from the valley (see the more detailled description below). It was going upwards over long stretches and partially steep. Normally no problem, but in the brutal heat I lost so much water that my supplies of 1.5 liters drinking water were far too short. I quickly ran out of water and lost power. It got so far that I suffered vertigo. Dehydration threatened a collapse, so I had a stop at the roadside. Little traffic here, and the few motorbikes coming along were mostly loaded with people or goods, and the locals only stared at me, sitting exhausted in the shade. Only one couple stopped, but they hadn't water and couldn't do much. I went on then, dragged myself another slope up when a merciful soul stopped and gave me a lift to Thmor Bang. That were the last six kilometers of the way; actually I made it until short before the village outskirts.

I never had that experience before. The dirt road through the forest makes already a considerable impact on the microclimate. The bare ground does not absorb the sunlight anymore as green plants do, but reflects a brutal heat. It comes together with the typical Cambodian dust who is permanently whirled up on these ways.

Another possible event in such a situation could be a sunstroke. A sunstroke happens, when the head get's overheated and the brain becomes so warm that it expands inside the skull. The skull itself consists of bones and does not expand with the brain, so, the brain get's increasingly squeezed against the inner skull. That leads to heavy misfunctions of the brain, which urgently needs to bee cooled down again. Well, a simple hat prevents a sunstroke.

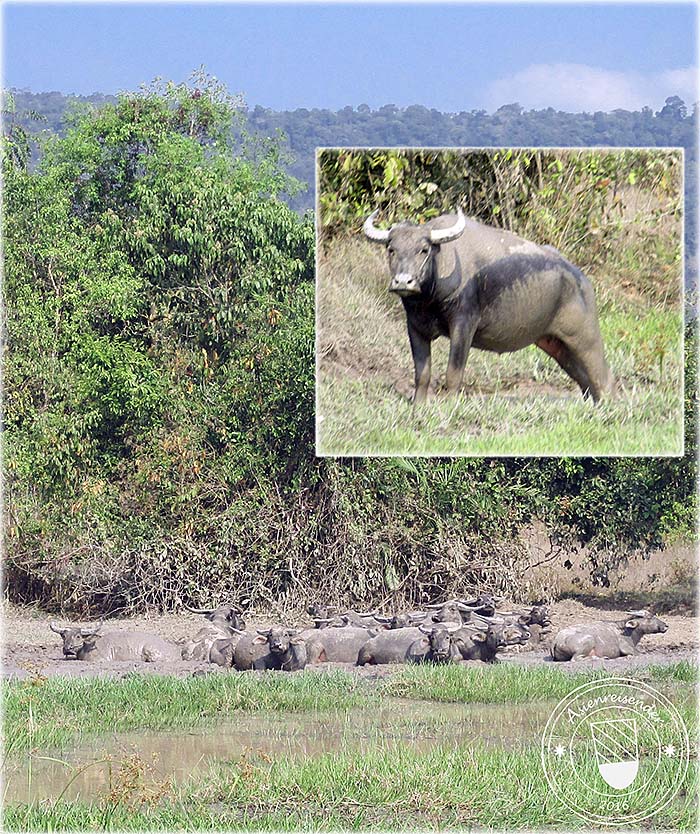

Water Buffalos on the Way

A herd of water buffalos, laughing at the hiker. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, 2/2016

8.

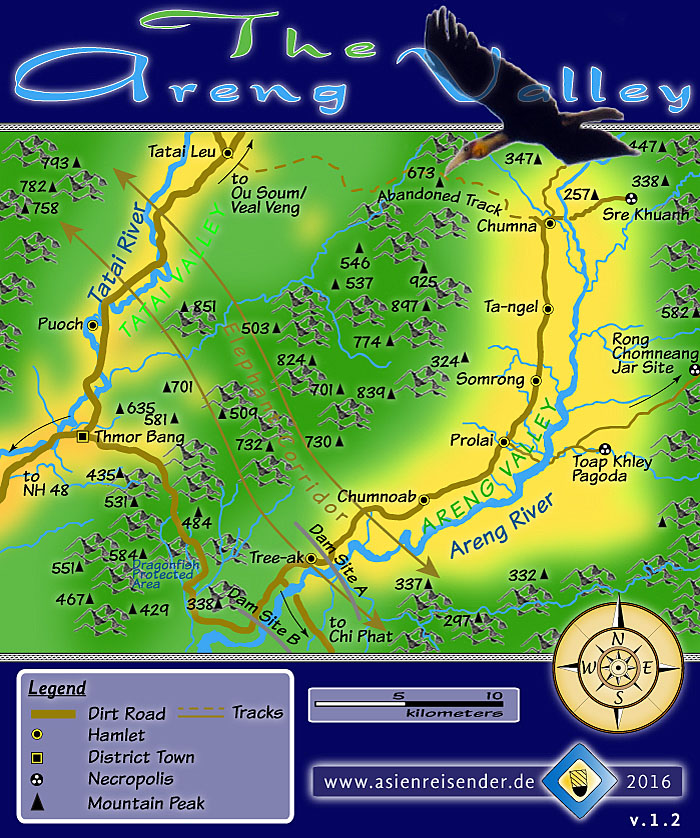

Map of the Areng Valley

Human settlements are usually founded at river banks. That is obviously a good place, for the river gives water supplies, serves as a drainage, a fishing ground and attracts many animals who come to the water for drinking or hunting. The water can be canalized for irrigation purposes. Besides, rivers are traditionally the oldest transport network in history, long before the first roads were established. It is therefore strange to see that all the six hamlets in the Areng Valley are a good distance west of the river placed.

The map is, to say that, not completely accurate. All the maps I found on the area differ from each other. Some differ extremely. I saw a map in Koh Kong which shows much higher mountain peaks around Chumna. Also the scale is to use with care. Nothing is clear in this country, nothing... Sketch by Asienreisender, 3/2016

Hiking in the Areng Valley

In a second visit I tried to see more of the fascinating landscapes of Areng Valley. My first idea was to walk to the jar site of Rong Chomneang, but since I wasn't happy with the local guides, it seemed to far and hidden in the forests to find. Crossing the Areng River east of Prolai, there were many tracks leading into eastern directions.

This fellow stuck closely firm to the stump and ned urgently help. No soul around, and his eyes already red, he might have stood for quite a time in the bare sun. Image by Asienreisender, 3/2016

My intention was now to find the little pagoda of Toap Khley, what shouldn't be too far from the river. An old women, who was busy on her new plot of burned forest confirmed that the place was there and gave me a hint. But, although I tried all the tracks who split right from the main track, I didn't find it. All I found there was a water buffalo who had a problem. He was self-trapped by winding some heavy plant material around his horns and stuck now very close to a tree stump. He couldn't move anymore and ned help. I managed to cut him free with my pocket knife, but he was pretty nervous about me coming so close to him, and I was also very nervous, because once having the animal freed it wouldn't have been a nice thing to be run over by a 200kg heavy, panicking animal. However, the procedure took about 15 minutes and afterwards he was completely calm.

Then I continued further eastwards. The landscapes change from secondary forest along the river to partially larger patches of savannah, grassland, bushes and forest again. Only far in the background are the higher mountains who border the valley. They are partially hard to see, because the smoke in the air is so thick that the sight is hindered. Everywhere are patches of land where recently fires burned, everything is blackened, dead, ashes. It looks spooky and sad.

I spent eight hours in the wider area here, walking seven of them with a break of one hour. In the southern background, most of the time, I heared permanently a motorchain. At one spot I found a recently logged tree. Fresh wood shavings lied on the ground, large logs still around.

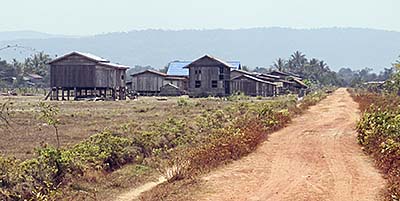

Prolai

One of the hamlets along the main road is Prolai. Image by Asienreisender, 3/2016

I came pretty deep into the forests east, and saw a great number of wooden animal traps. I destroyed any of them, and it became over the time quite a hard job to rip all the cut branches out of the ground; some of them stick very firm. I made also at any time clear that nobody was watching me, because it's pretty dangerous to disturb other peoples business. I didn't count them from the beginning on, but I guess I destroyed at least 30 traps, ripping them out of the ground and throwing them deep into the dense jungle. Actually that's the job of the rangers who are supposed to patrol these tracks. I saw two rangers in the ranger station in Thmor Bang - they spent a peaceful time in their hammocks at eleven at morning. They are Khmer and certainly don't want to come in trouble with angry villagers, who occasionally kill people who hinder them poaching, logging, dynamite fishing and so on. There are far too few rangers in the protected area, and they do too little. Besides, they need protection, because they come in conflict with police and army, who are involved in exploiting the nature.

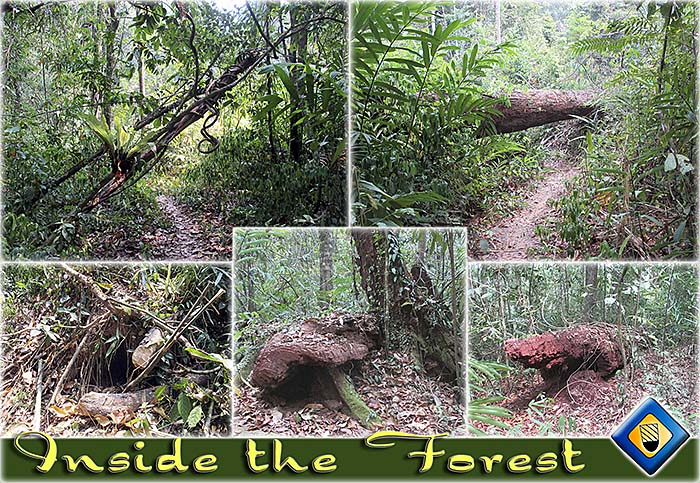

Inside the Forest

That's how it looks inside the forests. Sometimes the paths became very narrow, but seldom wider than on the upper two photos. To the right and the left are many holes who could be burrows of different animals. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, 3/2016

Next day I walked the road up to Chumna. This hamlet lies at the northern end of the valley. It is closed there by mountain peaks; the river, who is here quite small and shallow, comes anywhere through the mountains. I tried to find the former village of Sre Khuahn east of the river, but again failed. Villagers told me it were a 'bigger' place and had been evacuated by the Khmer Rouge. As it is always with the locals, they never give one a clue. One has to pull any piece of information out of their noses, and when not asking the right questions about significant information, because one is foreign here and does maybe not know about the significance, they would never tell.

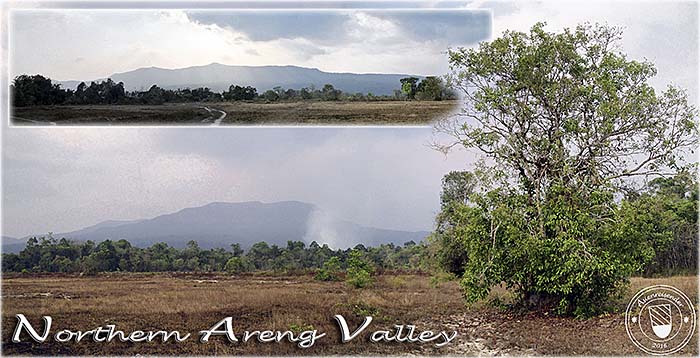

The Northern Section of Areng Valley

A typical scenery in the valley. In the foreground meagre grassland, completely exhausted, sandy ground, in the middle secondary forest and in the background the mountains who border Areng Valley to the north (main image) and the west (smaller image top). There is an imense haze in the air; both photos have been made about an hour before sunset. At noon the haze was so thick that the mountains were barely to see. Images and photocomposition by Asienreisender, Chumna, 3/2016

However, I walked some kilometers around there, most of the landscape here is secondary forest, but also savannah and grassland appears. Later, I spent a peaceful afternoon in my hammock at the riverbanks, watching the animals there and having a cooling bath. A few meters riverupwards some water buffalos did the same (swimming, not hammocking).

By the way, north of Chumna is, according to the owner of the only restaurant in this place, another jar site in the mountains. He told me it would be called Rung Aek.

Village Youngsters

Youngsters in Chumna. Image by Asienreisender, 3/2016

Before nightfall I went back into the hamlet and decided to sleep in a most primitive, half-open bamboo shack at the roadside. Soon the local owner appeared and demanded a price appropriate for a guesthouse.

Next day I planned to walk over the mountains westwards, leaving Areng Valley to Tatai Leu. A supervisor of US AID, who I met two days before, told me that there were a road or at least a track and it would be possible to go there. The villagers in Chumna, however, had pretty little of a clue about that. If they have to go to Tatai Leu, one told me, they would go on their [blasted] motorbikes, making the huge detour via Thmor Bang. In fact it was the fourth time here that I failed to find my way. Soon west of the hamlet all the paths end up on fields; here and there is another very small path leading into the forests, but which one is the right one? I tried for a time, but didn't find a way.

So, leaving Areng Valley meaned to walk the whole way back to Thmor Bang. Since it was late already and hot, I drank a few cups of tea in Chumna restaurant. The water tasted smoky and didn't do me good. Over the first few kilometers I felt sick in the stomach. That's probably because the villagers boil the water from their wells on open fires and don't put the lid on the kettle. The smoke touches the water's surface and causes the bad taste. Maybe not too healthy, either. Strange, that these people lack intelligence even in the most practical all-day affairs. I observed the same thing also doing the Batak People at Lake Toba. Bottled drinking water is rare in Chumna, and it costs more than petrol. I drink easily five liters a day in the heat when hiking.

Areng's Latest Outpost

That's Areng's most extended outpost on a peak which falls westwards down into the much higher situated plain of Thmor Bang. Image by Asienreisender, 3/2016

It's interesting, when driving one has so little sensitivity for the ups and downs of the terrain, for it goes so easy. As a walker one feels that the valley, when following the main road, is shortly south of Chumnoab slowly elevating. That stretches over kilometers, and over the longer distance it starts sucking. Tree-ak is the last place in the valley; short behind it one sees the high mountains close and the road becomes a serpentine, turning from now on rather westwards. And goes upwards. More and more. And now it really sucks. It goes over long stretches up, and more and more, and steeper and longer and steeper and longer. Behind the next curve it goes steeper and longer, and steeper and longer. One reaches a peak and thinks the worst is over, but it's just a short interruption. Soon later it goes again over long stretches steep up, and steeper and longer and steeper. Another peak but, no, it's not the longed-for end of the strain, instead it goes further on steep and steeper, and longer and steeper, again behind the next curve, and longer and steeper. No wonder that I lost so much water last time here in the brutal heat; this time I was better prepared. The difference in altitude must be several hundred meters, before one has finally left Areng Valley. At the very end of the almost endless ordeal comes a wooden post, which is the entrance to the much higher situated plain of Thmor Bang. This post was, by the way, used by the anti-dam activists to stop surveyors and construction workers to enter the valley. Having a stop here, pretty exhausted, I heared a tree falling in the forest behind. Logging goes on everywhere in Cambodia's forests. I don't think, they will last much longer. However, a few kilometers further lies the district town of Thmor Bang, actually also not more than an outspreading village. It is out of the so called protected zone and close to Tatai Valley. In Thmor Bang is a guesthouse for a rest for a night. This day I walked certainly about 60km.