Friedrich Gerstäcker's Journey on Java in 1851

Friedrich Gerstäcker (*1816 - 1872) was a German travel writer. He became famous after his first journeys to north America and his publications of his adventurous life there. He wrote and published a large number of books. In later years and aftermath Gerstäcker's writings were a model for adventurous travel novels of the 19th century, inspirating many other authors who followed him, including Karl May.

Friedrich Gerstäcker

In 1849 Gerstäcker started a great journey around the globe, starting in south America, followed by California, Tahiti and Australia. In 1851 he arrived in Batavia (Jakarta) on Java. One of his books is exclusively dedicated to his journey on Java.

He first describes the atmosphere and life of the Dutch establishment in Batavia. It's much about the saloon life of the privileged and decadent upper class of the colonial elities. Interesting to read that he had at the beginning some trouble with getting a visa and being allowed to travel further inside of Java. He suspects the Dutch authorities being concerned he could incite an uprise among the Javanese People. Besides it is an evidence of the fact that the Europeans, of course, brought the system of total control via papers, passports and permits into Southeast Asia.

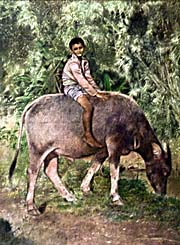

What's the thrill of hunting, except one needs food?! Image by Asienreisender, Surabaya, 2012

After an initial time in Batavia he left the capital and went to Bogor (in this time: Buitenzorg) and Bandung. Unfortunately he is wasting a lot of time with hunting activities there, describing it over long passages too much in detail. Hunting the Javanese rhinoceros and the Java tiger. Not only for knowing that both are meanwhile extinct, I don't appreciate it. It's about killing for fun or, as it is shining through, an abstract ambition ('I have to do it'). And don't tell me, dear reader, it's part of human nature. It's not.

Besides Gerstäcker mentiones that the Dutch administrations made it mandatory for everybody who killed a tiger to provide the tiger's fur to the administration. They got a reward of 15 Dutch gulden for a fur. He mentions also that the Java tiger was already seldom to see for many were already killed and the population was already shrinking. Tigers came in seldom cases near villages and killed cattle, or, in more severe cases, into the villages killing people. Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn described such an episode in his book 'Licht- und Schattenbilder ueber die Einfuehrung des Christenthums auf Java' (1858).

Climbing a volcano around Bandung is the much more interesting depiction Gerstäcker does, particularly when he describes the surrounding nature.

Java is coined by volcanos, which makes the landscapes so incredibly different from mainland Southeast Asia. Image by Asienreisender, here at Dieng, 2012

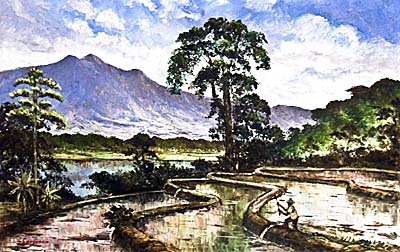

The Javanese People are mentioned as very friendly, hospitable, faithful and unspoiled. Gerstäcker sees clearly how exploitative the Dutch colonial system dealt with the Javanese. To build the road between Batavia and Bogor/Bandung the life of many locals was sacrificed. It was the ambition of the Dutch governor to finish the road within a certain time.

Gerstäcker's depictions of the Javanese supports my idea that the deprivation of the people of Java is rooted in the colonial past, later continued by the local elites. Though, one can not ignore the fact that the old Javanese feudal system was very authoritarian already. Gerstäcker describes also the sycophantic behaviour of the locals according their Javanese lords. We find that motive also in Ananta Toers novel 'The girl from the coast'. The Dutch took, of course, full advantage of it. In this time Islam spread out considerably on Java, as a counter movement against the foreign rule.

On the other hand is it several times mentioned how friendly, heartily and supporting all the Westerners on Java appeared to a stranger like Gerstäcker was one. That's absolutely no more the case in our days, where almost exclusively egocentric narcissits are travelling. Superficial live-style anarchism wasn't an option for the people of the 19th century, with a few exceptions in the very high nobility maybe.

I very much hoped to find Gerstäcker meeting Franz Wilhelm Junghuhn, who was living on Java in the same time and who was already a famous person. But I was disappointed. Junghuhn is only once remotly mentioned.

I was also disappointed to see that Gerstäcker didn't travel to neither Dieng nor Borobodur nor Prambanan. He didn't visit the Merapi nor the Bromo. In fact he missed the best parts of Java. That might have to do with the visa restrictions of the Dutch authorities of the time. Even the Dutch themselves, even when they were born there, complained about that. It was very difficult for anybody to get a visa which allowed him to travel further than from Batavia to Bandung. Besides Gerstäcker mentions that parts of Java weren't under control of the Dutch. He gives Solo (Surakarta) as an example.

Stamford Raffles, who did significant inventions on Java in the years 1811-14 and in which time as a governor Borobodur and Prambanan were (re-)discovered, isn't mentioned a single time.

It's also clear that Gerstäcker longed to go back home and didn't intent to stay much more time on Java.

Rice farming on Java in the old times. Image by Asienreisender, Surabaya, 2012

When Gerstäcker went back to Batavia, he decided to spend some more time there. He described a number of interesting things happened in the 'Dutch East Indies'. Among them is an execution. A local guide had killed a Dutch officer. These guides were, as Gerstäcker writes, not seldom forced into service for the Dutch due to gambling debts in which they were tricked.

The execution was a miserable event. The convicted appeared seemingly self-confident, didn't show any fear. The Dutch officer in charge was clearly in a hurry, for he seemed to have further plans for this day, didn't want to be bothered more than absolutely necessary with the annoying execution. A group of local people then embarrassingly mistreated the convicted before the execution on the way to the scaffold. The event was, as it was normally the case in former times, attended by a public audience. That was for the deterring effect, to show everybody what one has to expect when not following the rules. Gerstäcker tells that the nasty scenes were around in his head and dreams still for weeks after.

At the end Gerstäcker also describes his journey back to Europe on a sailing ship of the time. To travel from Batavia (Jakarta) to Bremen took him not less than 129 days in the first half of 1852. All the way around the 'cape of the good hope' at south Africa, for the Suez Canal was only opened in 1867.

Alltogether the book is clearly not a 'must read', but it's interest lies in the fact that it allows us to compare contemporary Java with the times of the mid 19th century. A time with no cars, no electricity, no computers and so on - but the same industrial process and the same social order we have was already in place. A process which clearly must have led to all the problems of world destruction we face since the 20th century and which is ongoing in an accellerating speed. Very few people of the mid 19th century saw that already coming - but there were some. Gerstäcker was none of them.