Richard Attenborough's Film Gandhi

"Generations to come will scarce believe that such a one as this ever in flesh and blood walked upon this earth."

Albert Einstein

"He died as he has always lived: A private man without wealth, without property, without official titel or others.

Mahatma Gandhi is not the commander of armies nor the ruler of vast

lands. He could not boost any scientific achievement or artistic gift.

Yet man, governments, dignitaries from all over the world have joined

hands today to honor to this little, brown man in the loincloth who led

his country to freedom."

Commentator on Gandhi's funeral ceremony

Of importance is the possibility that

the film will bring Gandhi to the attention of a lot of people around

the world for the first time, not as a saint but as a self-searching,

sometimes fallible human being with a sense of humor as well as of

history.

True greatness cannot be hidden behind mere ordinariness. Some subjects

are so pervasively great that no film, given a certain level of

intelligence on the part of the people who make it, can fail to catch

something of the essence.

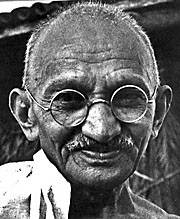

Such a subject is Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869-1948), the great Indian

political leader who used nonviolent resistance to win the Indian

subcontinent's freedom from the British Empire, and who lived to see

that dream split in the partition of India and Pakistan.

On independence day in August 1947, when someone used the word

"congratulations," Gandhi is reported to have said that condolences

would be more in order. Six months later, Gandhi, who was born a Hindu

but who preached the brotherhood of men under one God, was assassinated

in Delhi by a Hindu fanatic. His is one of the great stories of modern

times.

Gandhi, produced and directed by Richard Attenborough (Oh! What a

Lovely War, Young Winston), is a big, amazingly authentic-looking

movie, very sincere and aware of its responsibilities in the panoramic

manner of a giant post office mural. It has huge, rather emotionless

scenes of spectacle that are the background for more or less obligatory

historical confrontations in governors' palaces and, best of all, for

intimate, small-scale vignettes from Gandhi's life. The film follows

him from his days as a young lawyer in South Africa, through the

evolution of his political activism and asceticism, until his death at

the age of seventy-nine.

Gandhi, which opens today at the Ziegfeld Theater, is most effective

when it is being most plain and direct, like Gandhi himself. In Ben

Kingsley, the young Anglo-Indian actor who plays the title role, the

film also has a splendid performer who discovers the humor, the

frankness, the quickness of mind that make the film far more moving

than you might think possible.

Mr. Kingsley, a member of London's Royal Shakespeare Company, looks

startlingly like Gandhi. But this is no waxworks impersonation. It's a

lively, searching performance that holds the film together as it

attempts to cover nearly half a century of private and public turmoil.

Gandhi is least effective when it is dealing with historical events and

personages, especially British personages, who are portrayed by such as

John Gielgud, Edward Fox, John Mills, Trevor Howard, and Michael

Hordern. Some of them come very close to being cartoons, the sort of

Englishmen who are always identified by having either a teacup or a

whiskey glass in hand. The people who play Lord Mountbatten, India's

last viceroy, and Lady Mountbatten look remarkably lifelike but sort of

stuffed.

Somewhat better are the Indian actors who play Pandit Nehru (Roshan

Seth), Mohammed Ali Jinnah (Alyque Padamsee), and Gandhi's wife,

Kasturba (Rohini Hattangady). Athol Fugard, the South African

playwright, has one brief, effective scene as General Smuts. Ian

Charleson of Chariots of Fire has a small part as one of Gandhi's early

English supporters, and Martin Sheen turns up from time to time as an

American newspaper reporter. Candice Bergen is on hand at the end as

Margaret Bourke-White, the Life magazine photographer.

The film portrays the political events from 1915 until independence in

broad, "You Are There" style, sometimes with real dramatic impact, as

in the protests over the government's salt monopoly, but sometimes

perfunctorily, considering the awful nature of the events. This is

particularly true of the film's handling of the Amritsar massacre of

1919 when British troops were ordered to fire on hundreds of unarmed

Indians.

NYT Critics' Pick

By Vincent Canby

Published: December 8, 1982

Shortened by Asienreisender

Source: http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173BB12CAB484CC2B7799E836896&partner=Rotten%20Tomatoes

Salt from India, the Salt of the Earth

At Gandhi's funeral, expressions of sympathy pour in from all over the

world. "In his hands, proclaimed one Western commentator, humility and

simple truth were weapons more powerful than whole empires." In our

modern era replete with tyrants, weaklings and two-faced leaders, what

did Gandhi achieve to merit such praise? Plenty, brothers and sisters,

plenty.

While our reckless world threatens to erase Gandhi's legacy from its

collective memory, this film reminds us of his invaluable contribution

to peace, justice and the defence of human rights. At first an

undistinguished lawyer, Gandhi gained prominence as an opponent of

institutional racism in South Africa. After bringing the Smuts

government to reason, he returned home to wage another battle, this

time against British colonial rule, and succeeded once again. As

overwhelming as those victories were, they are almost unimaginable when

you consider the weapons Gandhi wielded against his people's

oppressors: instead of violence, he urged humility, patience,

discipline and civil disobedience. Though the target of constant and

excruciating abuse, he remained his intelligent and determined self,

willing to suffer with his followers in the name of truth and integrity.

Unlike many biopics, Richard Attenborough's epic film does not limit

itself to events. Thanks to John Briley's outstanding script and

powerful dialogues, it also examines the ideas and ideals that drove

Gandhi as a militant. His syncretic view of religion, mistrust of

politics and doubts when faced with the immensity of his task are ably

documented here. His frankness, love of the poor and openness toward

one and all are also evident in Ben Kingsley's magnificent performance.

As masterful as Attenborough's movie truly is, its weight rested

squarely on Kingsley's shoulders and he pulled off a miracle, clearly

deserving his Oscar for Best Actor. The all-star cast around him,

composed of Indian, British and American thespians, seconded him

beautifully in roles of reason, stubbornness, dignity or brutality. I

must warn you that, overall, the Brits and South Africans are patently

despicable while most of the film's decency and spiritual value is

contributed by Indians; on this account alone, it was fitting that a

British film set matters straight for our generation and the ones to

follow.

Without a doubt, GANDHI is a well-balanced and inspiring picture but

also a tough watch since it depicts many revolting and appalling

events; its last half-hour is disheartening but no less important to

our understanding of human nature. It explains some of today's

political realities in the Indian subcontinent, promotes virtues at

once universal and necessary and shows us how politics should be

practised in our era, not with polls and calculation but with

principles, self-control, firmness and an eye to the future. Its

lessons are timeless, stimulating and hugely effective.

Thus, if you are a true movie buff and you care about our world, I

strongly recommend that you spend three hours on GANDHI. You will never

forget the Mahatma, his radiant smile and innate generosity. Hail

Attenborough's masterpiece of art and humanity but, more than anything,

rejoice in Bapu's message and legacy!

Daniel Charbonneau, Province of Quebec

December 23rd, 2009

Slightly shortened by Asienreisender

http://moviebuffinslippers.blogspot.com/

Source: http://movies.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=EE05E7DF173BB12CAB484CC2B7799E836896&partner=Rotten%20Tomatoes