2.

The Customs of Cambodia

Zhou Daguans report on Angkor has a long and interesting history itself. It was written in a time after the author came back to China, up to 15 years after his return. He wrote it from his memory and confessed here and there that he couldn't remember certain facts. Memories are often playing false. So Zhou Daguan described the Nagas at the gates of Angkor Thom as nine-headed; in fact they have seven heads.

It's also to mention that the work is incomplete. What we still have is a fraction of the original only. Alltogether it's not much of a text. Nevertheless it's a valuable source of the life in medieval Angkor in the late 13th century.

All the fourty chapters are short and only few extend a bit over a single written page.

The Route to Angkor

The report starts with a short description of the course of a ship coming from Wenzhou to the Tonle Sap Lake and to Angkor.

The Walled City

Next Zhou Daguan described Angkor Thom as the 'walled city'. He mentioned all the main buildings as the Bayon and the Baphuon and the royal palace. Also Angkor Wat and a 'mighty stone tower' (Phnom Bakheng?) south of the city is mentioned. He wrote that dogs and criminals weren't allowed in the city. Criminals were recognized by missing toes, who were chopped off as a penalty.

The Royal Palace

He made an account of the royal palace and regreted that he couldn't visit many of the sights in the inner part, for it was 'so strictly guarded'.

It's Zhou Daguan who depicts the famous saga of the serpent in the Phimeanakas. According to that the serpent with nine heads [!] is the hidden lord of the empire. It's changing every night into a woman, "which whom the sovereign couples". Should the king fail to do so, a disaster was to expect; should the serpent not appear, the king would die soon.

Clothing

There was not much clothing in Angkor, but the bit of a dressing expressed very much the status differences of the people in this very stratified society. Who was allowed to dress how was very much regimented. Both genders wore merely a strip of cloth around the waist, the women showing bare breasts. For special, representative events the dressing code became a bit more complete. The people of Angkor went mostly barefoot. Women adorned themselves with bracelets and fingerrings and used perfumes.

Functionaries

A ceremony.

The highest functionaries Zhou Daguan mentioned, were the "ministers, generals, astronomers and other functionaries". Most of them were princes, and there must have been many princes, for the king had not only several wives but between 3,000 to 5,000 concubines and has probably produced a great reservoir of 'blue-blooded' offspring. Interestingly the high-priests are not mentioned as such. Religion has played a very prominent role in Angkor and the religious authorities were of great power.

The differences between the functionaries and their status was expressed in clothing, jewellry and other accessoires, including different palanquins.

Religious Groups

Interestingly there are Taoists counted among the religious men, not only Buddhists. Brahmins also play a role, but the dominant religion at the time was (Theravada) Buddhism. "Worship of the Buddha is universal", Zhou Daguan noted. There were no nuns, neither of Buddhist nor Taoist faith.

Taoism plays nowadays no role in Cambodia anymore; here and there appear Taoist temples to see in Malaysia. They are run by Chinese.

People of Angkor

The commoners are described as "coarse people, ugly and deeply sunburned. (...) It applies equally to the ladies of the court and to the womenfolk of the noble houses (...)". It's also mentioned that on the market larger groups of commoners tried "to catch the attention of Chinese in the hope of rich presents. A revolting, unworthy custom, this!" It's just like today with the tourists...

The Khmer of the time had no names, neither personal nor family names. The only replacement for a name was the weekday they were born. The Angkorean calender had seven weekdays, each of them had a certain meaning (with attributs as evil omens and so on). The Khmer also didn't held a record of their date of birth.

A cockfight. Gambling and animal abuse are only two of the many vices who are still common in Cambodia (and Southeast Asia generally).

(...) the Cambodian women are highly sexed. One or two days after giving birth to a child they are ready for intercourse: if a husband is not responsive he will be discarded. When a husband is called away on matters of business, they endure his absence for a while; but if he is gone as much as ten days, the wife is apt to say: 'I am no ghost; how can I be expected to sleep alone?'. Though (...) it is said some of them remain faithful.

(...) the Cambodian women are highly sexed. One or two days after giving birth to a child they are ready for intercourse: if a husband is not responsive he will be discarded. When a husband is called away on matters of business, they endure his absence for a while; but if he is gone as much as ten days, the wife is apt to say: 'I am no ghost; how can I be expected to sleep alone?'. Though (...) it is said some of them remain faithful.

Zhou Daguan:

'The Customs of Cambodia'

Siam Society, 1992

Cooking on an earthen stove in Angkor. The coalfire is supported with fans. The same kind of stoves are still in use in many Cambodian households.

Zhou Daguan also remarked that the Cambodian women would age very quickly. He sees the reason for that doubtlessly in the young marriages and too early pregnancies. He wrote that a Cambodian women of twenty or thirty years would be aged as a Chinese women twenty years older.

A very peculiar custom, to say the least, was the ritual of 'deflowering'. It's described as followed: girls in the age between seven and eleven (as richer the families as earlier the ritual) were handed over to a Buddhist or Taoist priest. The rich could determine a priest of their choice, the poor had no choise. The priests received rich presents of a variety of different goods; particularly the rich gave a small fortune to them. Poor families, whose daughters were eleven years already and who couldn't affort the presents, were often helped out by richer families, who saw this as 'acquiring merit'.

A great, noisy party was then arranged with a lot of accessories and a procession with palanquins and music for the priest. The music is described as deafening. The girl was waiting alone in a pavilion, until the priest eventually appeared to deflower her with his hands. Though, there remained doubts of that priest always used their hands only. However, the hands were cleaned then in a jar of wine, which was either drunken by the girl's family or they at least used it to stain their foreheads with it.

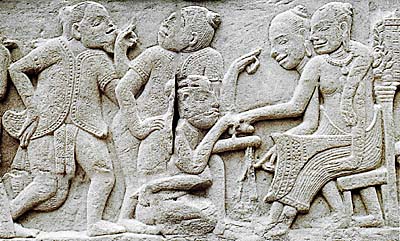

A market scene shown at the Bayon.

Next morning the priest went back home, richly escorted. The family had to buy [!] the girl now back from the priest with more precious presents. If not, the girl would become the priests legal property.

This story is pretty revealing for the abusive intentions who are inherent in (not only organized) religion. Also the status and wealth orientation fits into that pattern.

Interestingly the women were already, like today, the ones who run most of the small businesses. They didn't have shophouses but layed out their goods on blankets on the ground - as to see at many occacions still nowadays. And, as today, the authorities did collect taxes from the small stalls.

A growing number of Cambodians, Zhou Daguan noted, were learning to outwit the Chinese foreigners at the time and harming them considerably. Lying and cheating, cheating and lying. An old Cambodian custom... There must have been quite many Chinese settling in Angkor in that time already. A great many of Chinese goods have been dealt with in Angkor as well.

The notorious rice whiskey is also mentioned in Zhou Daguans record, among three other kinds of alcoholic drinks who were produced in Angkor.

A scene from Angkor. People transport goods, harvest fruits...

Aborigines

Zhou Daguan differs two kinds of aborigines in the Angkorean empire: such who know the Khmer language and were sold in the towns as slaves. That leads to the question if everybody outside the capital, towns and villages was without civil rights and could be enslaved?!

The other aboriginal people were, according to the description, the hill tribes who lived a nomadic life and didn't speak Khmer. He wrote very bad about them and described them as savages. He even wrote that murder in their gatherings were common. It seems that Zhou Daguan here trusted the bad talk of the Cambodians of his time and followed their prejudices. Factually he certainly didn't came in contact with these societies. Zhou Daguan also represents a Chinese who distincts himself from other ethnics who were for him generally 'barbarious'.

The slaves of Angkor. Hundreds of thousands of slaves must have been in Angkor, mostly captives from the never ending wars the empire led. Additionally there were slave expeditions sent into the mountains, enslaving people of the hill tribes in e.g. Ratanakiri and other mountainous regions.

Slaves

Angkor was a slave society, based on the ruthless exploitation of slave labour. Slaves were brought in from warfare or expeditions into the mountains, where people of the hill tribes were caught and brought into slavery. Slavery has a long tradition in Cambodia and was officially abolished in the French colonial time in the second half of the 19th century. One could argue, though, that slavery is still going on in an altered form until today.

Zhou Daguan wrote about his time, that wealthy families owned more than hundred slaves, others a few dozends and only the very poor didn't have slaves at all. The Khmer called the slaves 'Chuang', what meaned brigands and looked down on them as on low animals. Chuang was a very bad insult in the Angkorean society. Slaves were dealt with on the slave markets and certainly treated badly in general. In the case that slaves got children, the children would be the slaves of the owner of the mother for a live long.

The penalty for a slave who tried to escape and was captured was as brutal and barbarious as the whole Khmer civilization was.

Zhou Daguan does not tell anything about the state slaves who did the major work on the big monuments. The time of gigantomany was anyway over in his times. But state slaves for maintaining the state's infrastructure were certainly still there.

Language

The Khmer language is described as different from all the languages of the neighbouring people. The status groups had their own, distinctive kind of language as the mandarins, the priests and so on. Also in the villages were different dialects spoken.

Writings

Writing is an interesting matter, because the medieval Khmer had a written language (since long), but nothing of their writings overcame the time. Zhou Daguan noticed that the Khmer wrote on deer-skin, which was dyed black. They wrote on it with a kind of pencil which was a hollow stick and filled with chalk. The writing could be later wiped out and the skin used again. He did not mention palm leaves as writing material.

One of the outer libraries of Angkor Wat. The buildings survived, but not a single written word. Image by Asienreisender, 2006

Festivals

The festivals in Angkor are revealing parallels to the wasteful feasts of our times. The biggest of them was the new year festival. With great expenses towers were erected and fireworks and firecrackers were blown up. Zhou Daguan wrote that the rockets were seen as far as thirteen kilometers away. The whole, extremely noisy festival lasted a fortnight.

Every month there was another festival held. Zhou Daguan listed different reasons for what the festivals were held. They all were excuses for having noisy spectacles, as it is nowadays. And they all lasted several days, in one case he numbers it with ten days.

Interestingly he mentioned Khmer astronomers who were able to calculate eclipses of the moon and the sun.

Cambodian Justice

Prasat Suor Prat, a number of towers opposite the royal palace in Angkor Thom. Zhou Daguan told that opponents in trials were captured until one of them got ill as a sign of guilt. Historians doubt that, though. Image by Asienreisender, 2006

Many cases of dispute, even trife ones, have been brought to the ruler (means the emperor?! In this case he must have been quite busy with judging alone). The most penalties were done with paying a fine. In more serious cases convicted have been brought out of the west gate of Angkor Thom and have been burried alive.

Cutting off hands, feet or the nose were other punishments. In a case of adultery the offender was tortured until he gave all his property to the righteous husband.

Trials by ordeal were common. If an accused denied a theft his hands were forced into a pot of boiled oil. If the hands were after a time still unharmed, he was innocent. In case his hands were practically destroyed, he was seen as guilty and deserved it anyway.

Leprosy

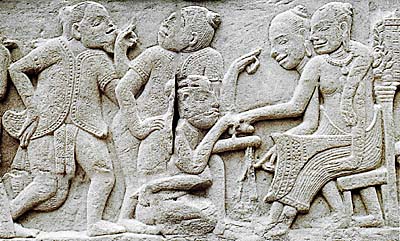

A sick person in Angkor on the lap of a woman. The man at the right might be a doctor.

Medicine was very incapable in medieval times. There must have been a high rate of leprosy in Angkor. Zhou Daguan wrote that a traveller would find many lepers along the ways. They also would eat and sleep among the healthy population - what must have made the disease considerably outspreading. Even one of the Angkorean kings suffered the disease and is still known as the 'leper king'.

Zhou Daguan gave his personal opinion of the reasons of the high leprosy rate. He believed that it came from taking a bath directly after having sex.

He also wrote that nine out of ten cases of dysentery ended fatally.

Funerals

Corpses of deceased were prepared and a ceremony was hold. The corpse then would be carried out of the town and left for the scavangers. If it was eaten up quickly by the beasts it meant a good omen, if not there were problems for the deceased in his afterlife.

The rulers were burried in Buddhist stupas.

Collecting Gall

A very peculiar event in Angkor was the exploitation of gall from living humans. Zhou Daguan described it as follows:

In times gone by, (...) collection of gall took place. The king of Champa annually exacted a large jar filled with thousands and thousands of human gall bladders. In dead of night men were stationed here and there in the more frequented parts of cities and villages. When they met people walking by night they threw over their heads a hood gathered together by a cord and with a small knife removed the gall bladder low down on the right side. (...) Only recently this practice of gathering gall was abandoned (...).

In times gone by, (...) collection of gall took place. The king of Champa annually exacted a large jar filled with thousands and thousands of human gall bladders. In dead of night men were stationed here and there in the more frequented parts of cities and villages. When they met people walking by night they threw over their heads a hood gathered together by a cord and with a small knife removed the gall bladder low down on the right side. (...) Only recently this practice of gathering gall was abandoned (...).

Zhou Daguan:

'The Customs of Cambodia'

Siam Society, 1992

Why was it the king of Champa? And what was done with the gall then?

Angkor's Army

Very interesting is also Zhou Daguan's short note of the Angkorean army of the time:

Soldiers also move about unclothed and barefoot. In the right hand is carried a lance, in the left a shield. They have no bows, no arrows, no slings, no missiles, no breastplates, no helmets. I have heard it said that in war with the Siamese universal military service was required. Generally speaking, these people have neither discipline nor strategy.

Soldiers also move about unclothed and barefoot. In the right hand is carried a lance, in the left a shield. They have no bows, no arrows, no slings, no missiles, no breastplates, no helmets. I have heard it said that in war with the Siamese universal military service was required. Generally speaking, these people have neither discipline nor strategy.

Zhou Daguan:

'The Customs of Cambodia'

Siam Society, 1992

This account does not sound really trustworthy; how could the empire, even when it was in decline already, be based on such a poor army? There were certainly well-equipped and trained troops; but in the compulsory military service the draftees were probably ill-equipped and presumably in a low state of morals.

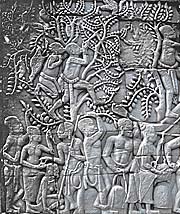

A military unit is marching. The dresses are also to see.

The King of Angkor

At the end of Zhou Daguan's short and fragmentary report we get a short idea of how it has been when the king appeared in a processon on the victory square in front of the royal palace and the 'terrace of the elephants':

When the king leaves his palace, the procession is headed by the soldiery; then come the flags, the banners, the music. Girls of the palace, three or five hundred in number, gaily dressed, with flowers in their hair and tapers in their hands, are massed together in a separate column. The tapers are lighted even in broad daylight. Then came other girls carrying gold and silver vessels from the palace and a whole galaxy of ornaments, of very special design, the uses of which were strange to me. Then came still more girls, the bodyguard of the palace, holding shields and lances. These, too, were separately aligned. Following them came chariots drawn by goats and horses, all adorned with gold, ministers and princes, mounted on elephants, were preceded by bearers of scarlet parasols, without number. Close behind came the royal wives and concubines, in palanquins and chariots, or mounted on horses or elephants, to whom were assigned at least a hundred parasols mottled with gold. Finally the sovereign appeared, standing erect on an elephant and holding in his hand the sacred sword. This elephant, his tusks sheathed in gold, was accompanied by bearers of twenty white parasols with golden shafts. All around was a bodyguard of elephants, drawn close together, and still more soldiers for complete protection, marching in close order.

When the king leaves his palace, the procession is headed by the soldiery; then come the flags, the banners, the music. Girls of the palace, three or five hundred in number, gaily dressed, with flowers in their hair and tapers in their hands, are massed together in a separate column. The tapers are lighted even in broad daylight. Then came other girls carrying gold and silver vessels from the palace and a whole galaxy of ornaments, of very special design, the uses of which were strange to me. Then came still more girls, the bodyguard of the palace, holding shields and lances. These, too, were separately aligned. Following them came chariots drawn by goats and horses, all adorned with gold, ministers and princes, mounted on elephants, were preceded by bearers of scarlet parasols, without number. Close behind came the royal wives and concubines, in palanquins and chariots, or mounted on horses or elephants, to whom were assigned at least a hundred parasols mottled with gold. Finally the sovereign appeared, standing erect on an elephant and holding in his hand the sacred sword. This elephant, his tusks sheathed in gold, was accompanied by bearers of twenty white parasols with golden shafts. All around was a bodyguard of elephants, drawn close together, and still more soldiers for complete protection, marching in close order.

The king was proceeding to a nearby destination where golden palanquins, borne by girls of the palace, were waiting to receive him. For the most part, his objective was a little golden pagoda in front of which stood a golden statue of the Buddha. Those who caught a glimpse of the king were expected to kneel and touch the earth with their brows. Failing to perform this obeisance, which is called sun-pa (sambah), they were seized by the masters of ceremonies (marshals) who under no circumstance let them escape.

Zhou Daguan:

'The Customs of Cambodia'

Siam Society, 1992